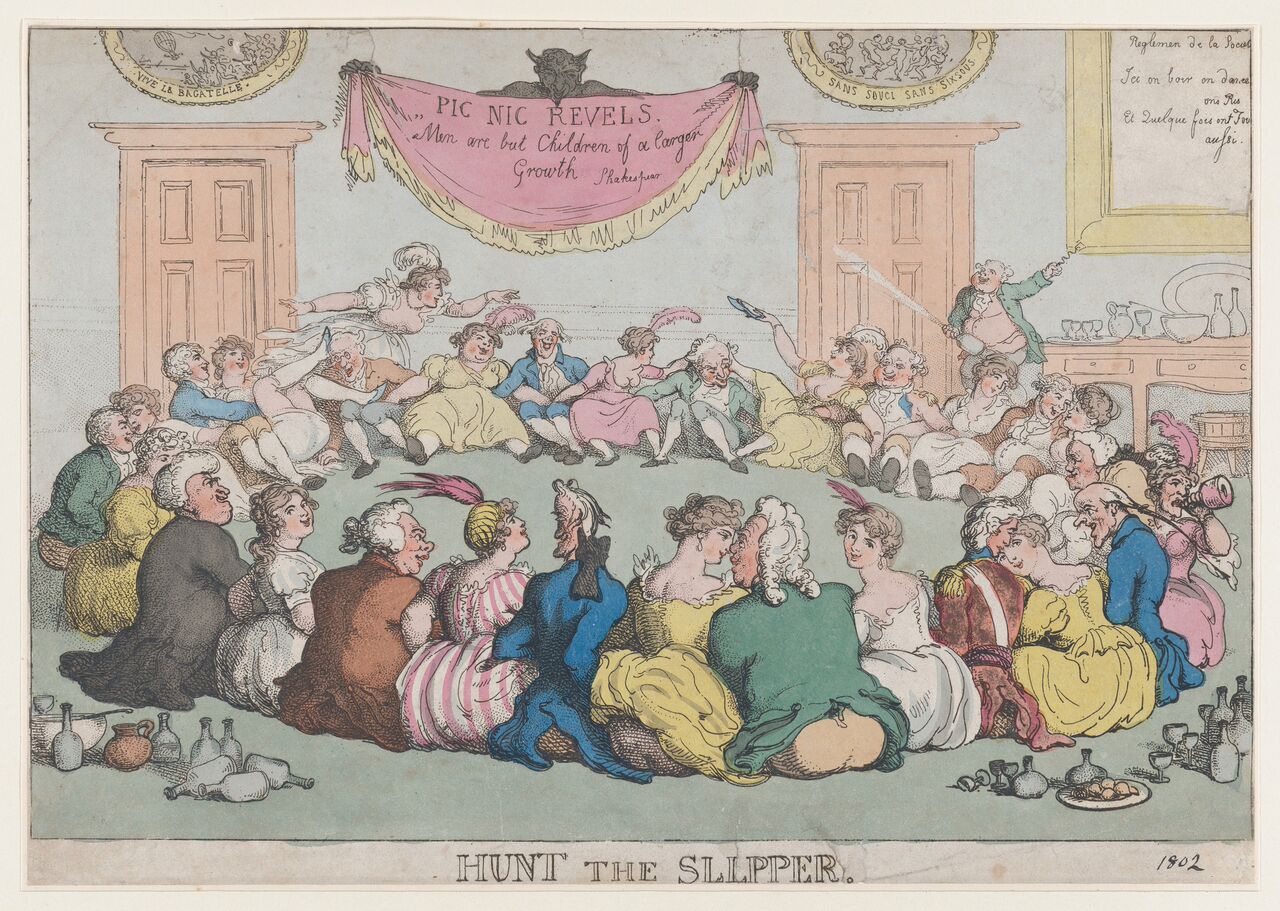

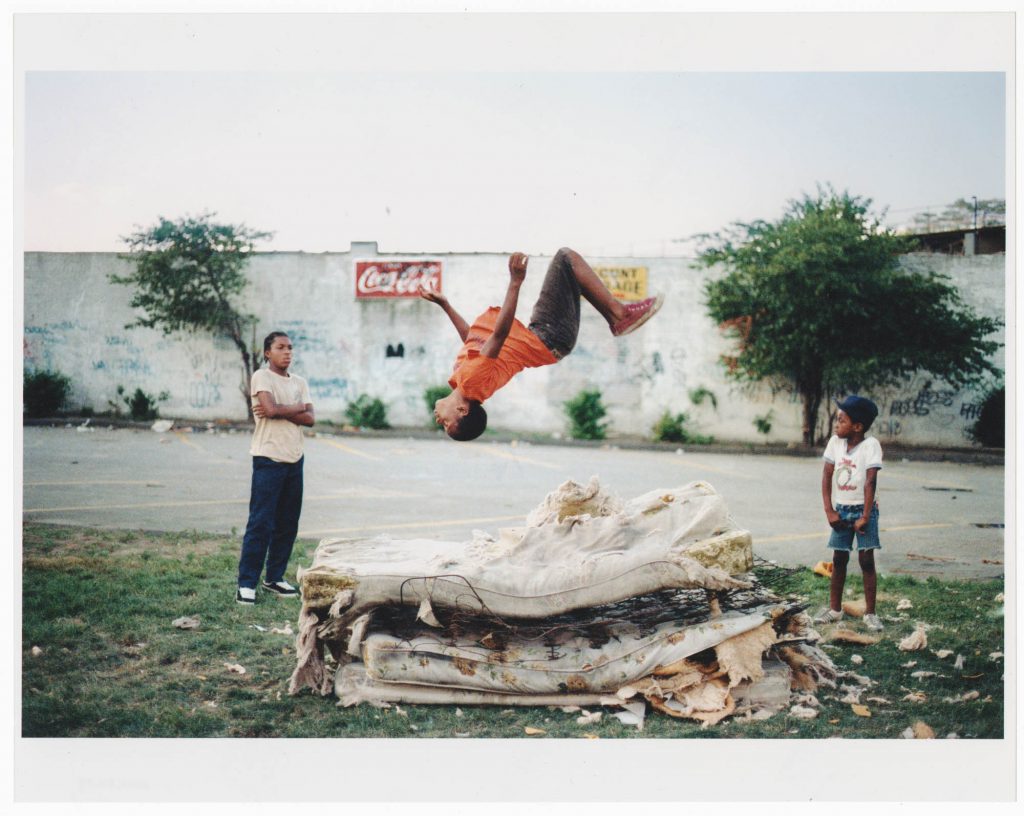

Albert Mobilio’s fictional stories are based on old-time games played in parlors, basements, and fields with balls, brooms, blindfolds, and cards. As winners and losers emerge from dodge ball, word games, and balloon contests so does the theme of our inner life as ceaseless competition. There is calculation, envy, humiliation, and joy, and there is always the next round when everything might change.

All players but Jack sit in a circle close together, with feet drawn up and knees raised so as to form a tunnel underneath the circle of bent knees. They pass a slipper from one to the other through the tunnel, trying to keep it hidden. Something about this ready-made tunnel strikes Sandy as unnerving—how easily a pocket of hiddenness can be made in plain sight. She laughs because everyone does yet stiffens in response to the newly made coolness below her bare legs, registering its kinship to caves, basements, and things unspoken.

The slipper isn’t glass or golden. Not one used for ballet or tightrope walking. An ordinary slipper. Torn seams, sole soiled from trips across the sidewalk to toss trash or the times it’s traveled all the way to the Bagel Delight on the corner. This slipper smells slightly of baby powder. Jack stands outside the circle and tries to follow the slipper’s covert passage and tag the player who has it. He doesn’t give a damn about the slipper or how he’ll be able to trade places with whoever he tags. What’s happening in his head is what he cares about: there seems to be a hockey puck sliding around the ice rink beneath the dome of his skull. Every movement—he bends down or charges forward—sends the disc caroming into the wall, the reverberation pulsing around his eyes. He can still taste the sweetish rum they were passing around, but not in his mouth—the taste rises up from his stomach. Where is that damn thing? The lights have been turned very low and he can’t even make out where people’s legs meet the floor let alone anything else. Better to follow the movements of shoulders than try to follow the slipper itself.

The bunched up thing comes Sandy’s way, the thin flannel cuff immediately familiar because the slipper is hers. She would have preferred not to use it—she might as well pass her socks around, too—but it’s her apartment and who else would have a slipper. Did Jess flinch the tiniest bit when it was in her hands? Sandy could swear she saw that. Could swear she saw a flicker of distaste. Jack darts this way and that, incorrectly tagging where he’s sure he discerned the telltale dip in Jess’ shoulder, then Frank’s friend, and that friend’s friend. He really needs to sit and let his headache have its way but just as he’s about to give up, he notices Sandy’s downcast eyes. She’s unaware, caught up in some faraway thought. He tags her, or really, because he has to lunge, he slaps her on the shoulder.

“You’ve got it,” he says. Without looking up, she offers the slipper. There’s the scent of baby powder. The inside worn smooth. He starts to put his hand inside as if it were a glove but he doesn’t. He shouldn’t. He knows that.

“Didn’t mean to hit you,” he says.

“That’s okay.” Sandy takes the slipper back. “Let’s hide something else.” ♦

(Image credit: Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1959.)