In the first of a two-part essay, writer and tech philosopher Tom Chatfield looks at an early progenitor of artificial intelligence.

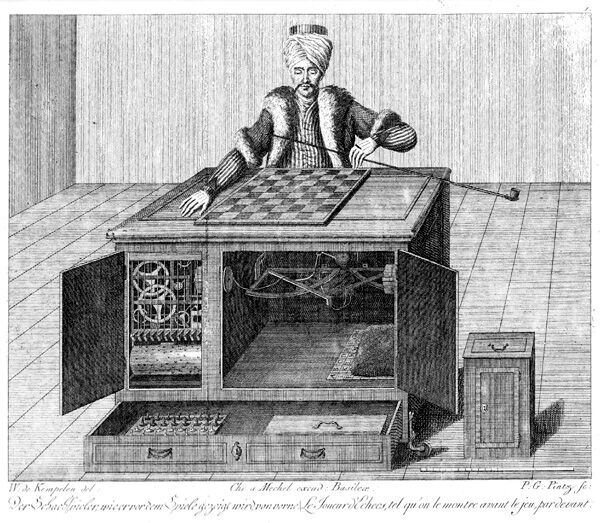

In 1770, the inventor Wolfgang von Kempelen displayed a mechanical marvel to the Viennese court. Watched by the Archduchess Maria Theresa and her entourage, he opened the doors of a wooden cabinet four feet long, three feet high and just over two feet deep, illuminating its interior by candlelight to display glistening cogs and gears. Seated at the cabinet was a life-size model of a man in Turkish dress—a turban and fur-trimmed robe. In front of the Turk, on top of the cabinet, was a chessboard.

Kempelen closed his cabinet and asked for a volunteer to play a game of chess against the Turk. It was astonishing request. Finely crafted automata had been entertaining royalty for centuries, but the idea that one might undertake an intellectual task such as chess was inconceivable—something for the realm of magic rather than engineering. This was precisely the point. Six months earlier, Kempelen had claimed to the Archduchess that he was utterly unimpressed by magic shows, and could build something far more marvelous himself. The Turk was his proof.

Count Ludwig von Cobenzl, the first volunteer, approached the table and received his instructions: the machine would play white and go first; he must ensure he placed his pieces on the centre of each square. The count agreed, Kempelen produced a key and wound up his clockwork champion, and with a grinding of gears the match began. To its audience’s astonishment, the machine did indeed play, twitching its head in apparent thought before reaching out to move piece after piece. Within an hour, the Count had been defeated, as were almost all the Turk’s opponents during its first years of growing renown in Vienna.

Humanity, for so long self-defined as the pinnacle of nature, had begun to feel less than mighty in the face of its own creations.

A decade later, Maria Theresa’s son, Archduke Joseph II, asked Kempelen to bring his creation to a wider public. The Turk visited Paris, London and Germany, inviting fervent speculation wherever it went. Among its losing opponents were Benjamin Franklin, visiting Paris in 1783, and—under its second owner after Kempelen’s death—the emperor Napoleon in 1809. Napoleon tested the machine with illegal moves, only to see the Turk sweep the pieces off the board in apparent protest.

It was, of course, a fraud—a magic trick masquerading as a mechanism. Behind the cogs and gears lay a secret compartment, from within which a lithe grandmaster could follow the game via magnets attached to the underside of the board, moving the Turk’s arm through a system of levers. In his book The Turk, the British author Tom Standage tells the story in captivating detail—noting that even the unmasking of its workings in the 1820s scarcely diminished the age’s fascination with the Turk. The image of man and machine locked in combat across the chessboard was simply too perfect—and too perfectly matched to a growing unease around technology’s usurpation of human terrain.

Humanity, for so long self-defined as the pinnacle of nature, had begun to feel less than mighty in the face of its own creations. The Industrial Revolution brought fire and steam as well as clockwork into the public imagination, together with anxieties that have echoed across society since: of human redundancy in the face of automation, and human seduction by new kinds of power.

Kempelen’s desire to make not simply a machine but also a kind of magic trick was no accident. The Turk set out to inspire belief, and had picked the perfect arena for persuasion: a bounded zone within which complex questions of ability and intellect were reduced to a single dimension. Sitting down opposite a modern reconstruction of the Turk in Los Angeles, Standage found himself surprised by how “remarkably compelling” the illusion remained, speaking to “its spectators’ deep-seated desire to be deceived.” Tools that can master a task are one thing—but it’s when they are also able to engage and enthrall that enchantment begins.

Long before digital computers had gained a genuine mastery of chess, one man devised a twentieth-century game with some remarkable similarities to Kempelen’s scenario. “I propose to consider the question, ‘Can machines think?'” wrote Alan Turing in his 1950 paper “Computing Machinery and Intelligence.” The trouble with such a question, he observed, was that answering it was likely to involve splitting hairs over the meaning of the words “machine” and “think.” Thus, he continued, “I shall replace the question by another, which is closely related to it and is expressed in relatively unambiguous words. The new form of the problem can be described in terms of a game which we call the ‘imitation game.’”

Turing’s imitation game entailed a conversation between a human tester and two hidden parties, each communicating with the tester via typed messages. One hidden party would be human, the other a machine. If a machine could communicate in this way, such that the human tester could not tell which of their interlocutors was machine or human, then the machine would have triumphed. “The game may perhaps be criticized,” Turing noted, “on the ground that the odds are weighted too heavily against the machine. If the man were to try and pretend to be the machine he would clearly make a very poor showing. He would be given away at once by slowness and inaccuracy in arithmetic.” Pretending to be human meant embracing limitations as much as showing strengths.

The answer was likely to involve splitting hairs over the meaning of the words “machine” and “think.”

Turing’s thought experiment suggested that, if the impression created were robust enough, the means of its achievement became irrelevant. If everyone could be fooled all the time, whatever was “really” going on inside the box ceased to matter. A game was the perfect test of intelligence precisely because it abandoned definitions in place of a challenge that could be passed or failed, as well as endlessly restaged. By excluding the world in favor of a staged performance, it made the ineffable conceivable.

Turing’s game is today played for real during the annual Loebner Prize, which since 1991 has promised $25,000 for the first AI that judges cannot distinguish from an actual human—and that convinces its judges that their other, human conversation partner must be a machine. No machine has got close to winning this award, but competing AIs are ranked in order of achievement. To the frustration of many AI specialists, the most successful chatbots tend to use tricks based on stock responses and emotional impact rather than understanding. Much like the grandly dressed Turk two centuries ago, the setup rewards the use of distractions and deceits: bogus bios, pre-programmed typing errors, hesitations, colloquialisms and insults. To win an imitation game, in certain circumstances at least, is not so much about perfect reproduction as targeted mimicry.

This is echoed in the world at large. If and when people are fooled by modern AIs, something more like stage magic than engineering is going on—a fact emphasize by the importance that companies like Apple, Amazon, and Google attach to quirky features which make their creations more appealing. Ask Amazon’s digital personal assistant Alexa whether “she” can pass the Turing test and you’ll get the reply, “I don’t need to pass that. I am not pretending to be human.” Ask Apple’s Siri if “she” believes in God and you’ll be told, “I would ask that you address your spiritual questions to someone more qualified to comment. Ideally, a human.” The responses have been pre-scripted both to amuse and to disarm. They’re meant to fool us into perceiving not intelligence but innocence—products too charming and too useful to provoke any deeper anxiety. The game is not what it claims to be.

Check out part two of Tom Chatfield’s essay here.