Albert Mobilio’s series of short fictions may be extrapolated from the rules of traditional games, but, in fact, they illustrate how time-honored and grounded in reality rules are. Missed the earlier stories? Read them here and here.

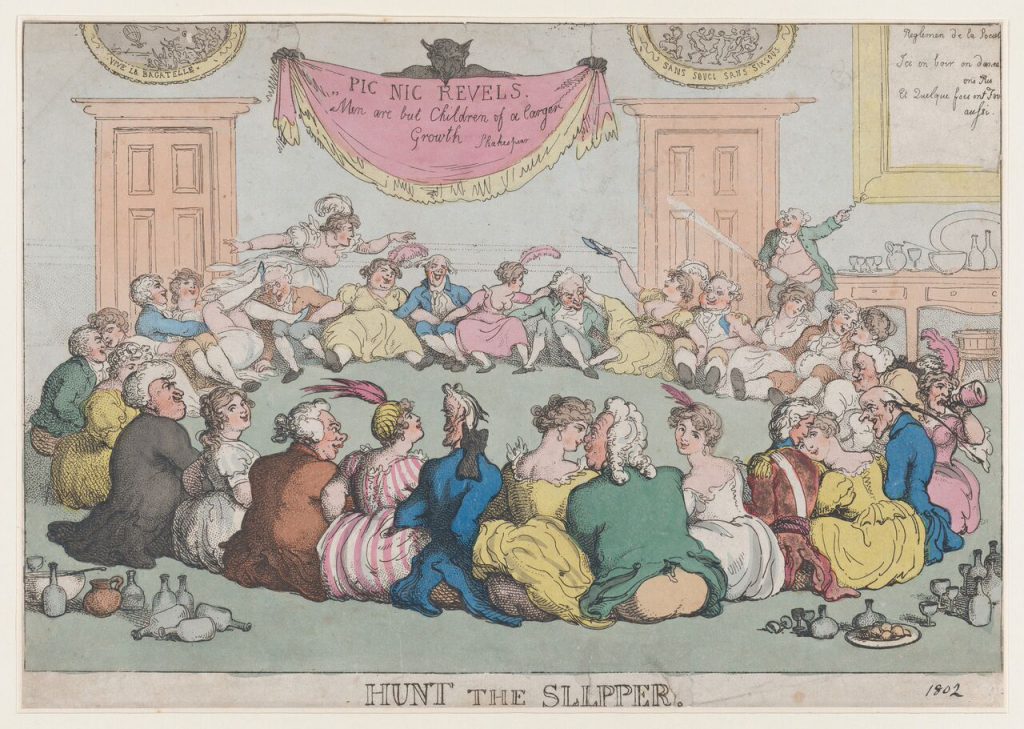

The fort is a line of gymnasium horses, parallel bars, curio cabinets, beat up lawn mowers, and other similar obstacles. The obstacles should not be too high, nor should they be too low, nor should they be just right, as such a notion appeals to a normative objectivity unrecognized as viable by players and game masters alike. Where necessary, the obstacles should be shrouded in black crepe, as befitting those objects (e.g., a tire, an ottoman, a treadmill, a corpse) that remind us that life itself is an act of mourning the relentless increase of the inanimate around us. Players form two teams, one in a line about twenty feet from the obstacles, the other just behind the assemblage. At a signal, the attacking team rushes forward and tries to climb. They must go over, not around. The defenders try to prevent the assault from succeeding. To do this they may go anywhere they choose. Maybe home, to a hot toddy and an uncracked copy of Middlemarch that will be read, it will, it will.

In any case, all manner of holding or blocking is permitted, anything, in fact, except hitting or other forms of aggressive roughness. Unexpected intimacies—kisses blown across the gym horses, suggestive winks while in a clinch with an opposition player, or frottage, but only light frottage, such as might be acceptable at a freshman high school mixer—are also permitted.

The defending team tries to prevent the attackers from getting over the obstacles. They may climb, push, or repurpose personal grooming items as weapons (only to be brandished in as much as one can brandish, say, tweezers). This is the way of the world: all against all, winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing. But the struggle is not so grim. If the attackers do not triumph in a pre-determined period of time—oh, about two minutes of appropriately Darwinian mayhem—then the two teams reverse positions. The shame of defeat flares but briefly in the players’ inmost selves; they will surely strive again and some Homer—could it be that ginger-haired lass who smells faintly of doused church candles—may perhaps someday sing of their brawny exploits. ♦

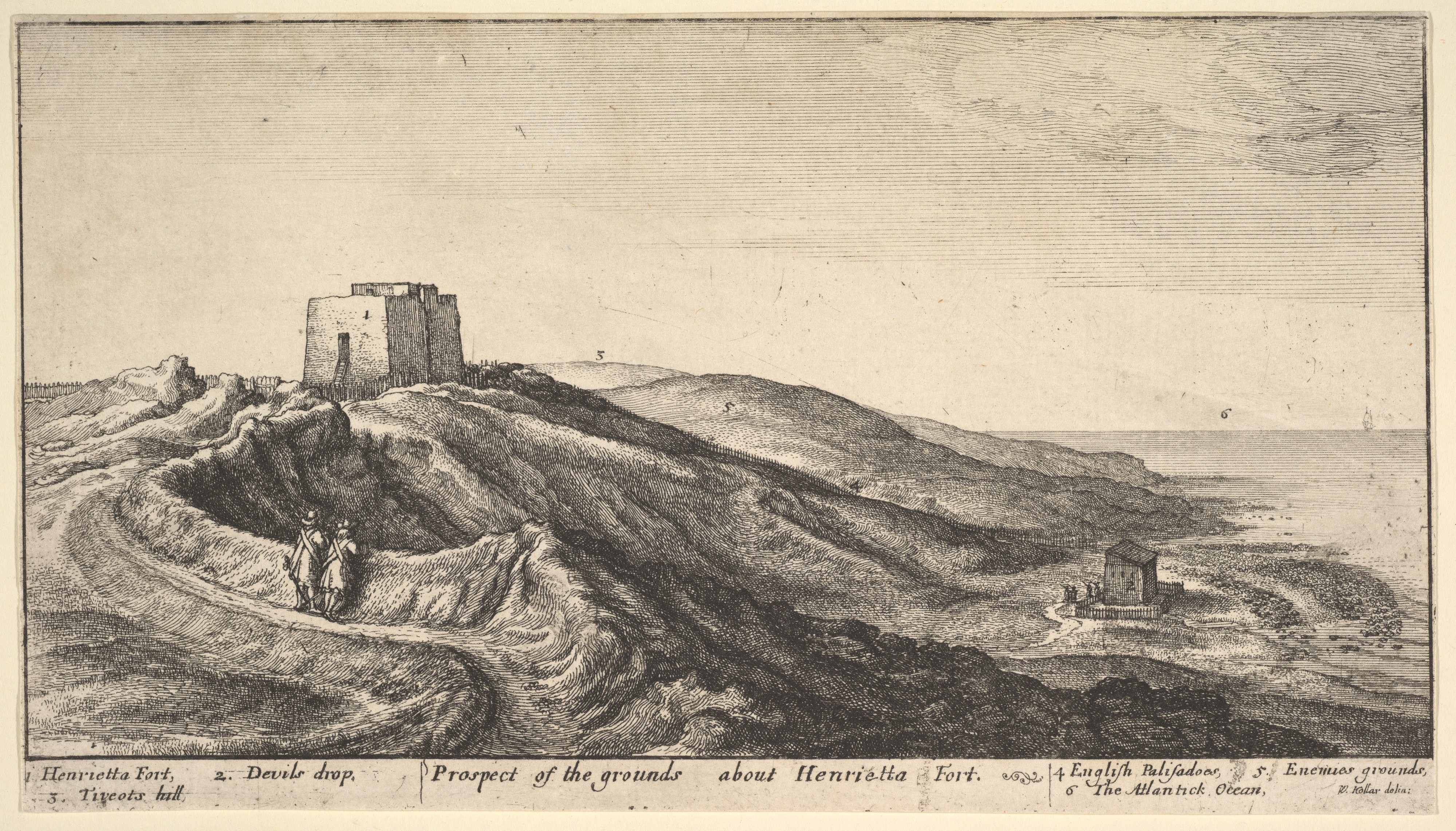

(Image credit: Wenceslaus Hollar, Tangier Views, about 1670, etching. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.)