Lydia Gordon, assistant curator, takes a look at Salem’s board game history and finds gaming treasure in the museum’s collection.

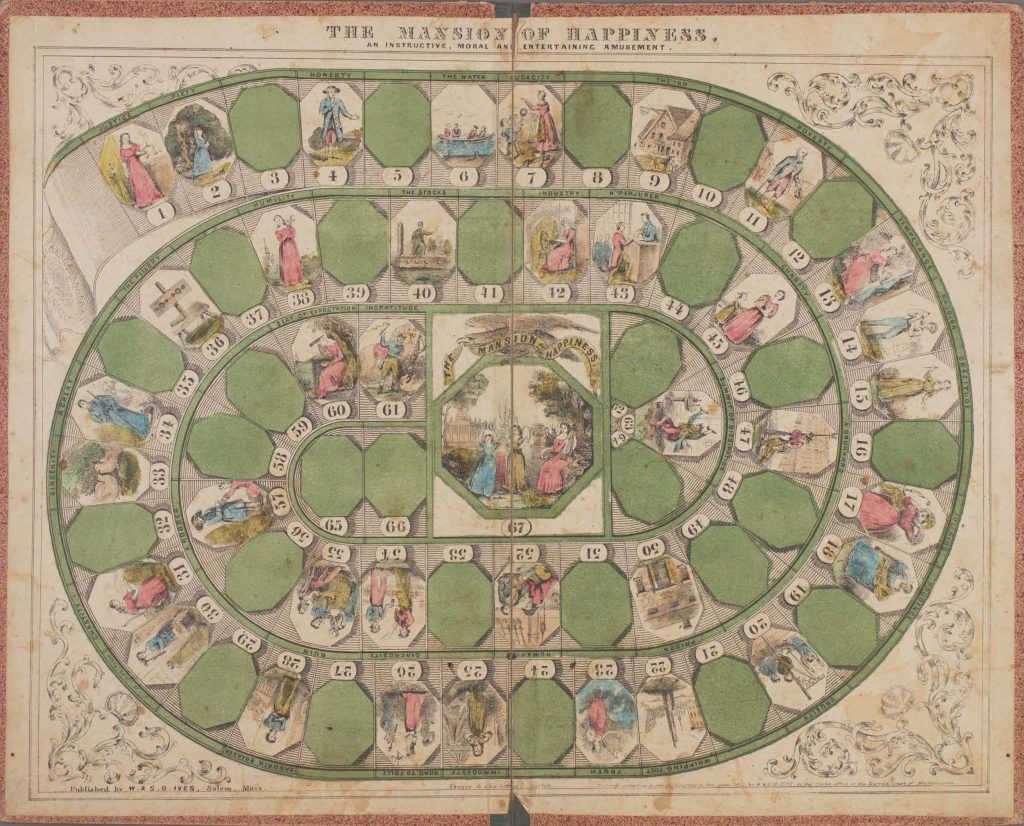

In 1883, sixteen-year-old George Swinnerton Parker (born 1866 in Salem, Massachusetts) was bored. A lover of board games, Parker had become restless with the available options of his time, including the highly successful and proselytizing The Mansion of Happiness. This track game included sixty-seven spaces through which players would journey to arrive at the titular manse in the center of the board. In addition to counting, players could also partake in “An Instructive, Moral & Entertaining Amusement” as they tried to advance towards the mansion quickly by landing on spaces marked “Piety,” “Honesty,” “Humility,” or “Generosity,” while avoiding the dangers of “Audacity,” “Cruelty,” and “Ingratitude.”[1] Sound familiar? In the twentieth century, Milton Bradley Company rebranded the game to create what is now the classic Life.

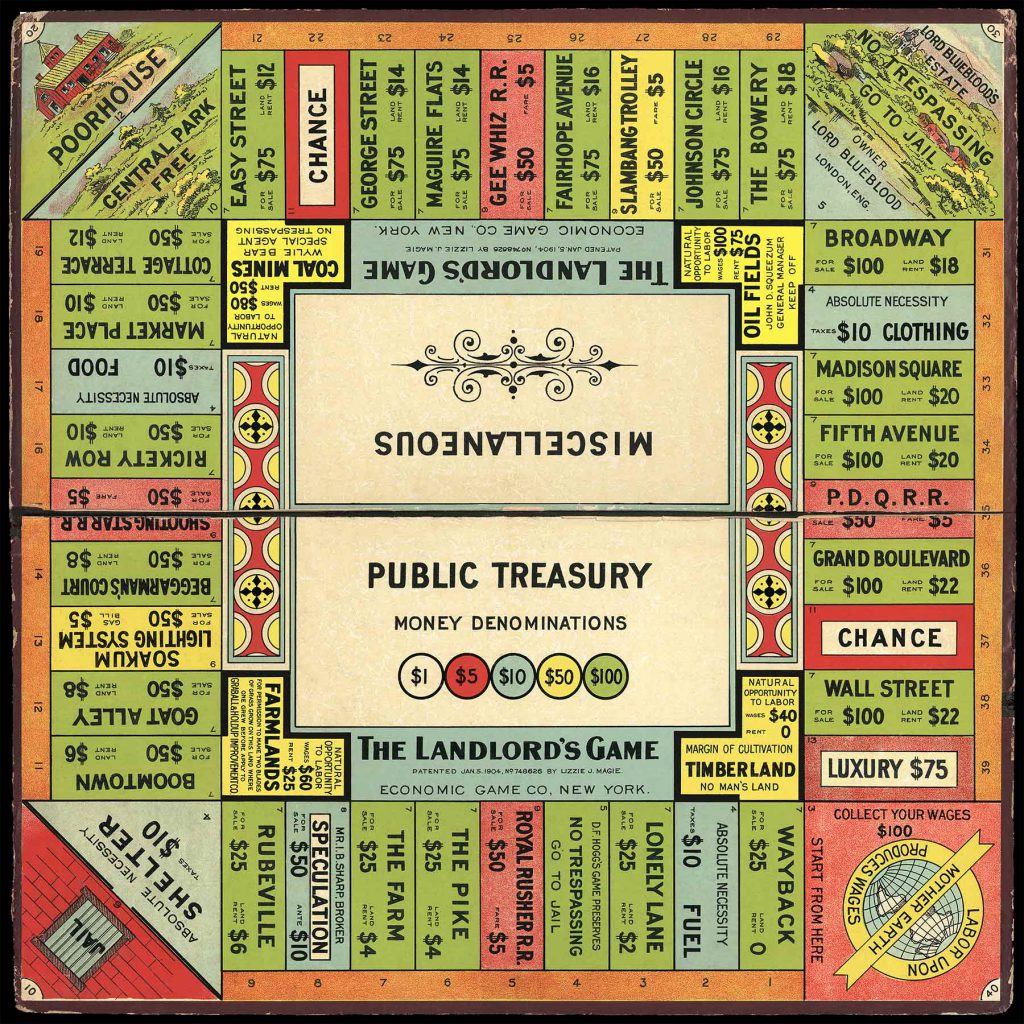

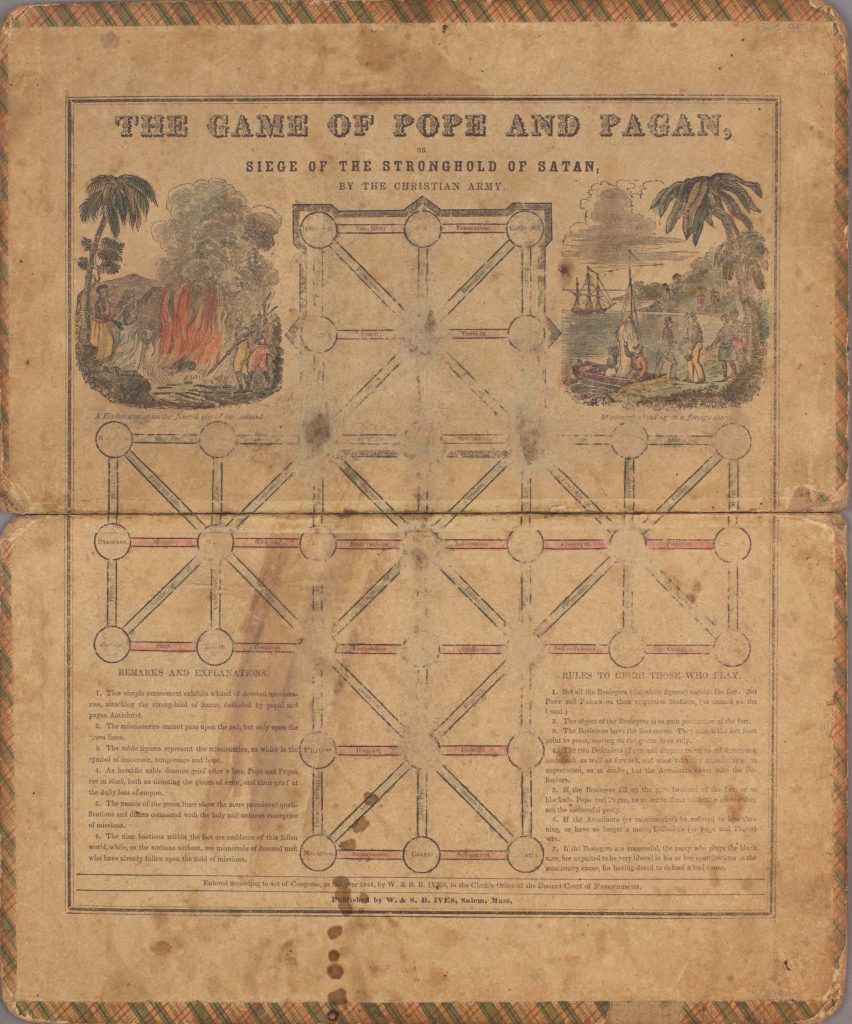

The game of piety was originally developed in Italy during the sixteenth century and later published by England’s Laurie and Whittle in about 1800. Anne W. Abbott of Beverly, Massachusetts, contributed to the development of The Mansion of Happiness, an Instructive, Moral, & Entertaining Amusement, published by the Q. & S. B. Ives Company of Salem, in 1843. Beginning in 1823, Stephen and William Ives had founded The Q. & S. B. Ives Company as Salem’s printing company. They published early track games while maintaining a long publishing record for The Salem Observer (1828–96), Salem’s Charter (1853), and even the East India Marine Hall Corporation’s by-laws (1826). Immediately following Mansion of Happiness, Q. & S. B. Ives Company published The Game of Pope and Pagan or Siege of the Stronghold of Satan by the Christian Army in 1844, a game based on the struggle of Christian missionaries to overcome Satan and paganism (they also released the card game Old Maid around this time).[2] In this questionably titled and generally offensive game, Robert Rath notes how, “[The Game of Pope and Pagan] depicted “half-unclothed ‘natives’ gathering around a roaring fire.”[3]

No wonder young Parker was bored. By 1883, he was living in a world where new manufacturing processes were invented, developed, and implemented. Parker had witnessed first hand this shift to industrial society. Born at 103 Essex Street to Captain George Augustus Parker and Sarah Hegenmen Parker, George was the youngest of three brothers. As Salem’s maritime trade dried up by the mid-nineteenth century, his father moved the family to Medford, Massachusetts, where he worked as a merchant and real estate agent.[4] By 1870, George Augustus Parker’s wealth had depleted. The man suffered from Bright’s disease and passed away in 1876 when his son was just 10 years old.[5] Now residing with his widowed mother, aunt, and uncles in the family’s large Medford home, the youngest Parker son turned towards his older brother Charles, then just twenty-three, of Salem for support. Charles was living in a local boardinghouse and working his way up at a fuel wholesaling firm.[6] With brotherly encouragement, George moved back to Salem with his mother into a much smaller home at 8 Mall Street, leaving behind extended family in Medford, in order to pursue a better life.

While George S. Parker’s own childhood was riddled with sickness and the loss of his father, he held a passion for thrilling and new playful experiences. The concept of childhood—in which both play and study helped shape future productive adults—was becoming widely adopted.[7] Parker’s desire for secular games reflected the cause and effects of industrial society, including human initiative over divine submission. So at age sixteen, he developed and sold his card game Banking door to door in Boston while on approved leave from high school. Banking was a game of supposition, free will, and trade: players received loaned cards from the bank only to repay with interest. Players earned profits and formed financial alliances, all while being encouraged to betray one another in order to advance one’s own interests.

In 1885, Parker bought the rights to Anne W. Abbott’s 1840 card game Dr. Busby and several other games, including a reissue of Mansion of Happiness. He opened a toy store at the corner of Salem’s Franklin and Washington streets in 1887, the site of the current Hawthorne Hotel. As business grew, his brother Charles joined the company in 1888. The brothers renamed their store Parker Brothers and moved to 182 Bridge Street. In 1893, third brother Edward Parker joined the company, relocating one last time to 190 Bridge Street.

The incorporation of Parker Brothers occurred on December 19, 1901. The company went on to open offices in London, Paris, and New York to great success, even through the Great Depression, due to the development of Clue, Risk, and Monopoly.[8]

George S. Parker was an avid supporter and former director of the Essex Institute, one of PEM’s precursor institutions founded in 1848 with a mission to preserve and publicize the history of Salem while overseeing natural history collections, historic homes, a library, and public museum. Parker often invited his highly regarded colleagues to lecture at the Essex Institute. It is within this legacy that George S. Parker’s grandson, Randolph Barton (born 1932) became president of the Essex Institute while serving as the last CEO of Parker Brothers. Barton was instrumental in the 1992 merging of the Essex Institute and the Peabody Museum into what is today the Peabody Essex Museum (PEM). PEM’s Barton Gallery is named in honor his parents, Robert B. M. Barton (1903–1995) and Sally Parker (1907–2000). At PEM, play is part of our DNA.

A particular Parker Brothers legacy can be discovered in the PlayTime exhibition. Parker Brothers developed a precursor game to table tennis, or ping pong, in 1896 called Pillow-Dex. This game invited players to bat inflated balloons back and forth across a string stretched over a table. One would win by landing the balloon on their opponent’s side ten times in a row.[9] Martin Creed’s Work No. 329, 2004, on loan from Rennie Collection in Vancouver, invites a comparable experience.

While Parker Brothers played a major role in developing Salem’s identity and community, Parker Brothers was in poor shape by the 1960s. In 1965, General Mills approached the company about a buyout that became official in 1968. Ranny Barton continued to serve as president of the company through 1984. Today, Parker Brothers (along with Milton Bradley Company) have been consolidated as part of Hasbro, Inc., with headquarters in Pawtucket, Rhode Island.

In addition to the objects mentioned above, PEM holds many Parker Brothers games in our collection, including Tommy Town’s Visit to the Country, Authors, Sherlock Holmes, The Wonderful Game of Oz, Star Reporter, Dealer’s Choice, and E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial.

Lydia Gordon will be moderating an upcoming panel, Game Changers: Women Activists in Digital Space, at PEM on Saturday, May 5, at 4:15 pm. Join us for this special PlayTime conversation with artist Angela Washko, scholar and activist Susana Morris, and game designer Jane Friedhoff. The panel is made possible by the George Swinnerton Parker Memorial Lecture Fund and offered in conjunction with the Present Tense Initiative.

[1] “90 Years of Fun: The History of Parker Brothers, 1883–1973,” Instructive and Amusing: Essays on Toys, Games, and Education in New England (Salem, MA, Essex Institute, 1987), 138. Original tapes from Fox’s interviews are in our collection and at Salem State University.

[2] Essex Institute, Instructive, 141.

[3] Robert Rath, “Board Games were Indoctrination Tools for Christ, then Capitalism,” waypoint, Vice, November 30, 2017.

[4] Philip E. Orbanes, The Game Makers: The Story of Parker Brothers From Tiddledy Winks to Trivial Pursuit (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2004), 2.

[5] Orbanes, The Game Makers, 3.

[6] Orbanes, The Game Makers, 6.

[7] For more on this, see Hugh Cunningham, The Invention of Childhood (London: BBC Books, 2006).

[8] “90 Years of Fun: The History of Parker Brothers, 1883–1973,” Instructive and Amusing: Essays on Toys, Games, and Education in New England (Salem, MA., Essex Institute, 1987), 154–55.

[9] Margaret Hofer, The Games We Played: The Golden Age of Board and Table Games (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2003).

(Image credit: Parker Brothers, Star Reporter (detail), 1955, Peabody Essex Museum, 136.201.)