How does playing with racial identity reinforce contemporary minstrelsy? Scholar and activist Susana Morris looks at the practice in art and culture from the Br’er Rabbit stories to pop star Miley Cyrus.

Comedian and writer Paul Mooney often says, “everybody wants to be black but nobody wants to be black.” To be sure, Mooney is known for provocative claims and bold language in his own standup and with his work with Richard Pryor, but this statement is not just a colorful play on words: it also describes the strange dance of desire and repulsion regarding blackness in the American cultural imagination. When divorced from actual black bodies, historical markers of black embodiment—from supposed sexual prowess, to proficiency in sports, to full lips and curvy figures, and other markers—are often viewed as fun, playful ways for non-blacks to change their appearance or to take on a new identity. This desire to embody aspects of blackness explains Miley Cyrus’s attempts at twerking, Katy Perry’s baby hair and cornrows, and Kylie Jenner’s new lips, hips, and behind, not to mention Rachel Dolezal’s so-called transracial identity. When the trappings of blackness imply the possibility of being cool, sexy, and authentic even if for a small moment in time.

Playing with blackness in online spaces can show up as what Lauren Michele Jackson calls a type of “digital Blackface,” or the “various types of minstrel performance that become available in cyberspace,” wherein non-black people use memes and GIFs with famous or anonymous black people to illustrate moments of feeling sassy, angry, lazy, petty, and the like.1 Digital blackface has become a sort of shorthand (not unlike using emojis) in social media, personal messaging, and even in digital journalism. Perhaps inserting a GIF of Oprah giving away cars on her show or Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt actor Titus Burgess gasping at a computer screen can convey “I am really excited” or “I’m very shocked” better than the words themselves. Or perhaps it is something about the “exaggerated” expressiveness that their blackness permits is speaking a language that plain English simply cannot.

Viewing, consuming, enjoying, and profiting from black bodies in pain has been an American pursuit from the days of black-face minstrelsy.

Blackness in whiteface is playtime, an American sport. But it’s not a wholly American pastime. Take for instance, German figure model Martina Adama, who underwent an extreme chemical tanning process and other surgical procedures to “become” a black woman. For Adama, “becoming a black woman” is as easy as child playing dress up: tan skin just so, purchase bodily enhancements, add curly wig and—voilà!—one can become a black woman. And when she is tired of the experiment charade—or when it is no longer lucrative—she can go back to living as she had before.

Blackness as a commodity that non-blacks can use to play dress up and escape their own dull reality is not just a twenty-first-century phenomenon. Langston Hughes—bard of the Harlem Renaissance—jokingly referred to the era as the time “when the Negro was in vogue,” referring not only to the style and substance of the art, dance, music, and literature that came out of the era, but also to the scores of whites who came uptown to slum it in the black part of town, eat black food, dance, and sleep with black people, before heading back to their tidy white lives. In The Black Interior, poet and essayist Elizabeth Alexander notes that, “Black bodies in pain for public consumption have been an American national spectacle for centuries. This history moves from public rapes, beatings, and lynchings to the gladiatorial arenas of basketball and boxing.”2 Put another way, viewing, consuming, enjoying, and profiting from black bodies in pain has been an American pursuit—indeed, a key part of American popular culture and art—from the days of black-face minstrelsy.

At the same time, the desire to embody and appropriate blackness also has a dangerous underbelly. This phrase also explains Officer Darren Wilson coded language in justifying his killing of unarmed teenager Mike Brown; that Wilson thought Brown “psychotic” and “hostile,” that he “looked like a demon” and “grunted” and “charged” toward him like a wild animal.3 Wilson’s account sounds less like he is a protecting the suburbs of St. Louis and more like he is hunting big game on the African savanna. Maybe for him and others like him, there is little difference. So while Mike Brown’s black life did indeed matter, his death became a spectacle.

Recognizing and embracing blackness in popular culture is not necessarily problematic in and of itself. It is the cavalierness with which blackness and, by extension, black people are treated that is the problem; when we play with people and their culture as if they are discardable objects, in fashion for a time and then out of fashion the next.

Blacks have been accidental, or rather unwilling, muses in art and popular culture in America almost since the country’s inception. Take for instance the figures of the sambo, the uncle, and the mammy, popularized in the first half of the nineteenth century. This mythological trio of the lazy but lovable shirker, the benign patriarch, and the fat, jolly matriarch were perfect for an antebellum America intent on depicting slavery as a benevolent, albeit peculiar, institution that rehabilitated savages and enabled them to be what God intended: “hewers of wood and drawers of water.”4 Everything from paintings to advertisements and bric-a-brac, not to mention popular songs, theater, and eventually film featured this unholy trinity of black figures. And although at their very heart these figures represented chattel that had as much legal right and standing as a glass pitcher, a chandelier, or a cow, they were often illustrated as playful or at play. For example, despite being a servant for life, the sambo is frequently depicted as a lovable slouch that loves naps and gets into hijinks because of his desire to cut corners and play rather than work. The uncle figure, such as an Uncle Remus, is a master storyteller who entertains white children with stories of tricksters like Br’er Rabbit. The mammy is devoted to cooking and cleaning for her white family, enabling the leisure of the people who owned her without complaint.

After a hard won emancipation, led by decades of agitation by free and enslaved blacks and a cohort of liberal and radical whites, these figures remained but stood alongside newer, more sinister depictions of blacks, such as the hyper-sexualized black buck and jezebel, that underscored the fear of newly empowered free blacks. Still, the old trifecta never fully went away, especially as newer mediums such as film took hold, alongside nostalgia for “simpler” days. These depictions of black folk have become engrained into the very psyche of American culture

Because of this contentious history, the notion of blacks embracing play has been a fraught one.

In the late nineteenth century, respectability politics arose as an antidote to these problems. According to historian Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, respectability politics was conceived of by black Baptist women and eventually spread beyond them to large swaths of black communities.5 The strategy behind respectability politics was for blacks to present themselves as the most respectable in their speech, comportment, attire, and family life. They would not appear silly, playful, or unserious. This would eventually earn them respect, favor, and full citizenship among the whites who both feared them and who controlled most aspects of society. Needless to say that this strategy was only partially successful; indeed, particularly during the nadir of black life—the time during and after the instantiation of the black codes that saw the rise of white supremacist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan and lynchings—being respectable and successful just might have made one the target of hate.6

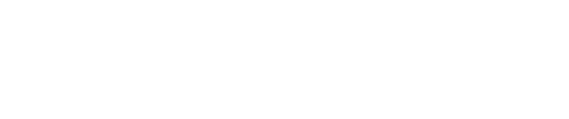

Because of this contentious history, the notion of blacks embracing play has been a fraught one. But the history above is just one side of the history. Just as slavery apologists were framing fictional portrayals of blacks at play, enslavers were cracking down on certain types of dance, music, and celebration, as they recognized their transgressive possibilities. Black folk have spent centuries defying rules and expectations about how to express joy, sadness, and laughter. They reinvented how to play.

Read on with the second half of Susana Morris’s piece on PlayTime artist Mark Bradford.

1 Lauren Michele Jackson, “We Need to Talk About Digital Blackface in Reaction GIFs,” Teen Vogue, August, 2, 2017, http://www.teenvogue.com/story/digital-blackface-reaction-gifs.http://www.teenvogue.com/story/digital-blackface-reaction-gifs.

2 Elizabeth Alexander, The Black Interior (Minneapolis, MN: Graywolf Press, 2004), 177.

3 U.S. Department of Justice, “Department of Justice Report Regarding the Criminal Investigation into the Shooting Death of Michael Brown by Ferguson, Missouri Police Officer Darren Wilson,” March 4, 2015, https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/opa/press-releases/attachments/2015/03/04/doj_report_on_shooting_of_michael_brown_1.pdf.

4 The Bible was often used to justify American chattel slavery. This phrase from Joshua 9:23 refers to the curse of slavery that Joshua put on the Gibeonites. He proclaims that they will be forever held in bondage to the Israelites for their sins. Racist antebellum preachers and theologians often used this verse and others to point to the Biblical foundation of slavery.

5 See Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham’s Righteous Discontent (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994) for more on the foundation of respectability politics.

6 See the work of nineteenth century journalist Ida B. Wells for more on this phenomenon.

(Image credits: Jamel Shabazz, Flying High, 1981, Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, gift of Jamel Shabazz. © Jamel Shabazz. Then NAACP President Rachel Dolezal speaking at a rally in downtown Spokane, Washington, May 1, 2015. Photo by Aaron Robert Kathman, on Wikicommons. Neave Parker, Brer Rabbit is thrown into the briar-patch and outwits Brer Fox in the Tar Baby episode, from The Tales of Uncle Remus, 1953, Art and Picture Collection, The New York Public Library, courtesy of the The New York Public Library.)