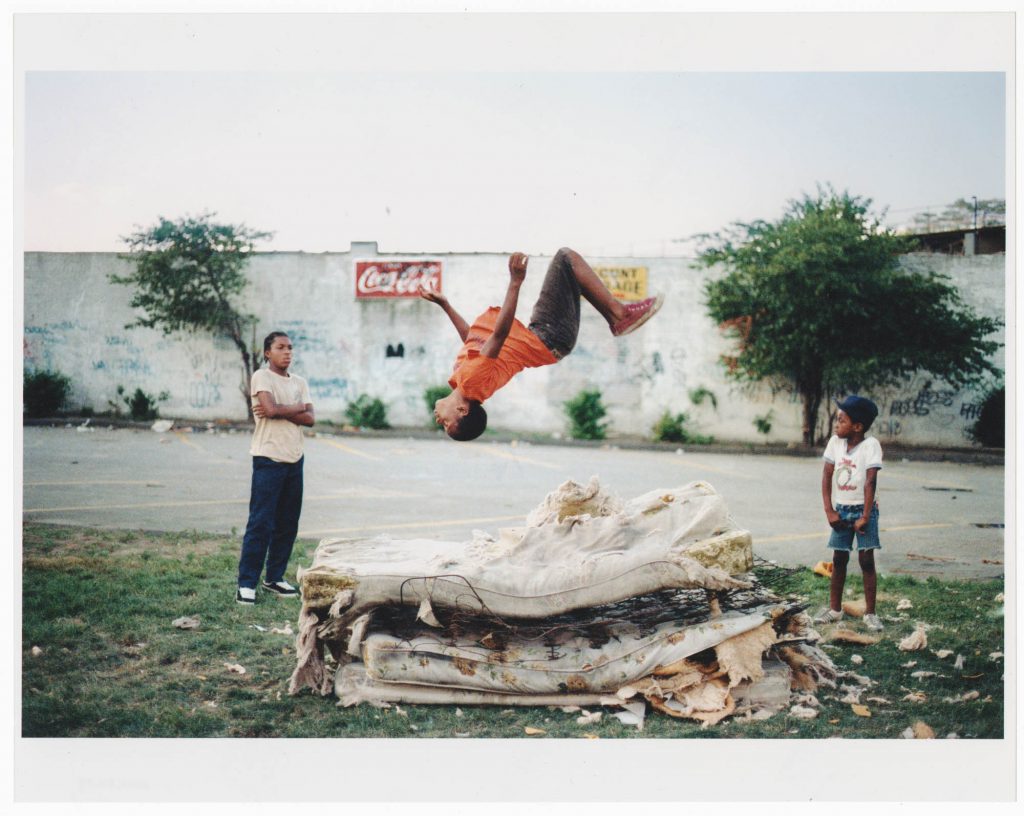

Anthropologist Stanley Thangaraj found camaraderie and cultural awareness through basketball. Can it help others feel more welcome in America?

In spring 1994, when we were students at Emory University, Kumrain invited me to play pick-up basketball, along with his friends Mustafa and Qamar in the hopes of forming a team for the Indo-Pak Basketball Tournament in Greenville, South Carolina. Mustafa, Qamar, and Ali lived outside Atlanta near historic Stone Mountain, once home to the Ku Klux Klan. As an Indian American, my close African American friends, liberal white friends, and other South Asian American friends all lived in Dekalb County, Fulton County, and Cobb County. Mustafa’s family lived in Gwinnett County, which was outside the perimeter demarcated by the I-285. It was held as common sense that few people of color traveled outside the perimeter. Upon meeting, playing basketball, and being dominated by Mustafa on the makeshift court in his parents’ driveway, I immediately realized the joy of male bonding with fellow Indian and Pakistanis in Georgia. I decided to join Mustafa and his mostly Muslim Pakistani American peers; we formed the team known as the Atlanta Outkasts, a name inspired by the popular Atlanta hip hop group OutKast. From the very onset, black style, black aesthetics, and hip-hop culture were instrumental in how we, as young immigrant men, crafted our identity and embodied “cool.” As Team Atlanta Outkasts, we played together for more than fifteen years.

This kind of love for athletics, maybe especially for basketball, was not unique to us. Two other Atlanta teams had gathered to compete at that weekend tournament, one of which—a majority Sikh team—reached the finals of the tournament. Malik, a founding member of the Outkasts, knew several of the members of the Sikh team, Krush, from their college days at the Georgia Institute of Technology. The other team, Crescent Moon, was comprised of men from Al-Farooq Masjid—pious Muslims, as demonstrated by their long beards and performance of salat (prayer). Mustafa and Qamar, at this point in their lives, did not embody the same level of piety: they partied hard, drank alcohol, used recreational drugs, and were outside the boundaries of Muslim respectability, even though many members of both teams attended mosque together. Regardless, one can see how the religious centers such as the Sikh gurdwara and Muslim mosques (masjids) in Atlanta, just like the major Christian churches, catered to and supported basketball as a means to raising young men within the fold of American identity.

Players take great joy in the male-bonding space of basketball, a space in which they affirm and are affirmed as athletes and men.

The types of camaraderie and competitiveness at the tournament were incredible; it gave me chills. I had harbored my own stereotypes of Indians and Pakistanis in the United States as being un-athletic; my own ego had convinced me that I was an exceptional athlete and therefore unlike other Indian Americans. However, the players and teams at the 1994 tournament forced me to reconsider my own biases. I felt like an outsider and yet so comfortable. It was a surreal experience. Never before had I been surrounded by a slew of such talented South Asian American basketball players. When I played intramural basketball with an Indian American team at Emory in my freshmen year, I had met only a few very strong players, but the Indo-Pak Tournament was an experience of its own. I could not stop smiling with both a realization of my Indian identity as athletic and being part of this basketball universe, but I also felt great pressure to play my best. South Asian American basketball excellence was no longer exceptional but rather simply routine in this setting. Here, as I’ve also observed in the Indo-Pak basketball circuits of Chicago, Atlanta, Washington, DC, and Dallas, players take great joy in the male-bonding space of basketball, a space in which they affirm and are affirmed as athletes and men. The sweet sound of the swish, the crossover move, a no-look pass, viciously blocking a shot, and the forceful dunking of the ball resulted in such unadulterated joy.

There was a desire even in this space of athletic parity to still be seen as exceptional.

However, in other basketball spaces, Indo-Pak players had to negotiate being stereotyped as either not American or “manly” enough. In sleeveless shirts and with sweat glistening off their athletic bodies, the players took pleasure in translating their musculature and bodily movements into basketball excellence. These men were also simultaneously claiming their American identity by playing basketball, which is so quintessentially American. Whereas the common assumption about the South Asian American man is that he is good for cricket, ping-pong, or the spelling bee, these basketball tournaments and pick-up games offer a reprieve from being culturally typecast as nerdy, not manly enough, or as un-American. The young men took delight in out-competing and beating their co-ethnic peers. There was a desire even in this space of athletic parity to still be seen as exceptional, as the model of the athletic South Asian American man.

An oasis like this also presents other political possibilities. When I was researching the Indo-Pak Basketball circuit in Washington, DC, and Maryland in 2008—the year Barack Obama became the first African American president—there were explicit conversations on the court that were loudly stated now. A few hours after the election, Mustafa texted me, “Now it is time for reparations,” a reference to centuries of unpaid black slave labor. Meanwhile, at the pick-up games in Maryland with members of the DC Indo-Pak team Maryland Five Pillars and their African American peers, players shared their experiences of racism while traveling and living in various places across the United States. Thus, instead of treating the election of Obama as an absence of racism, it became an opportunity on the Indo-Pak basketball court to talk explicitly about how South Asian Americans and African Americans are treated in the U.S. These moments of basketball on the co-ethnic-only circuits allow young men of color a chance to hope and desire another tomorrow, as seen with the photo of Mo Hoque of team NY D-Unit. It is an opportunity to offer a rendition of American identity that could be more welcoming. ♦

(Image credits: Courtesy of Ginash George, Indopak 2017, Chicago.)